Nikos Konstandaras

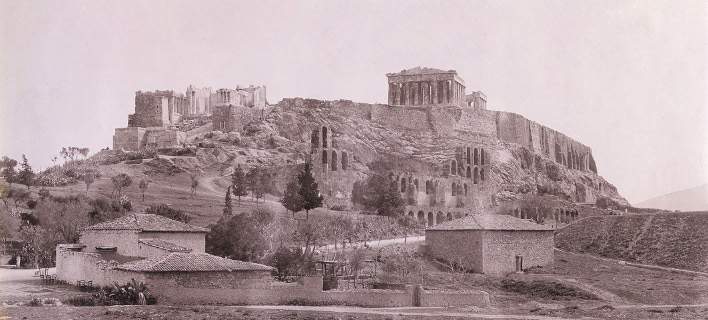

Syntagma and Lycabettus Hill, 1865. Much of what Edmond About describes after a two-year stay in Greece, during Otto’s reign, is still relevant. Greece remains a puzzle, both for foreign visitors and the Greeks themselves.

Syntagma and Lycabettus Hill, 1865. Much of what Edmond About describes after a two-year stay in Greece, during Otto’s reign, is still relevant. Greece remains a puzzle, both for foreign visitors and the Greeks themselves.

The new Greek edition of Edmond About’s “La Grece contemporaine” has been translated as “Otto’s Greece” so as to “correspond with the precise historical time of the original’s ‘Contemporary Greece,’” notes translator Aristea Komninelli. The book, originally published in 1854, could have kept its original title without misleading anyone – because much of what the French journalist and novelist describes and comments on after a two-year stay in Greece, during King Otto’s reign, is still relevant. Greece remains a puzzle, both for foreign visitors and for the Greeks themselves: How can a nation with so many skills and virtues be so incapable of creating an effective state, thus condemning itself repeatedly to poverty and debt?

The book, in Komninelli’s fluid and witty translation (2018, Metaixmio Publications, 442 pages), is a guilty pleasure. It elicits laughs through its depiction of familiar traits and behaviours, but also provokes melancholy by showing that the suffering of the country and its people is chronic, perhaps incurable. It provides a caustic and often humorous look at a nation that was still blinded by the light of freedom after centuries of darkness and remained trapped in a vicious cycle of administrative dysfunction, division and corruption, where robbers and state functionaries could trade places easily, where foreign powers exploited the Greeks’ passions but also lost their capital when they loaned it to the new state. The questions that About raises are the same as those we could ask today. How is it that 166 years after this book was written, nearly 200 since the start of the War of Independence, the Greeks continue to torture themselves and to burden their country with the same senseless modes of behaviour?

Bitter Truths

The book may be easy and entertaining to read but it is difficult to accept the bitter truths that it reveals, when it describes things that were just as inexplicable then as now when it functions as a fixed point in time for us to judge our own “contemporary Greece.” Exasperated by the fact that the Greek government does not exploit the country’s rich forests, and does not reorganize its agriculture, About comments: “The country, without being very fertile, could nourish two million people. It has 950,000 and it cannot feed them.” He adds that he cannot provide a precise figure for the arable land because he does not know it. “King Otto and his ministers are just as much in the dark, as they have not created a land register yet.” Greece still does not have a land register.

About’s arrogance and his mockery of the Greeks, whom he often presents as caricatures, become annoying and can raise questions as to his objectivity. But this uneasiness is secondary to our sense of familiarity with what he describes. “It is an axiom for the Greeks that all means of acquiring wealth are acceptable; successful theft garners praise, as it did in ancient Sparta; the clumsy are pitiful; those who are caught blush only because they are ashamed at having been caught,” he writes. About is most sarcastic about King Otto and his court, and about Greek politicians (who at the time were very closely tied to either England, Russia or France). It is clear that he is influenced by his country’s disputes with the other two powers. For him, the Bavarian king and his queen remain German and they grant the Greeks only the freedoms that the Greeks themselves win through violence, he comments.

“For all this, they reward us by arranging the robbery of our allies and the piratical attacks on our ships”

He notes Greece’s lack of gratitude, despite the huge amounts of money and the military power that France has provided: “For all this, they reward us by arranging the robbery of our allies and the piratical attacks on our ships.”

In his prologue – which presents About in the context of his time and describes his book’s reception – writer Takis Theodoropoulos notes, “About’s clear view of things does not flatter our collective narcissism, and so for a long time we had placed him in the ranks of the anti-Greeks, among those whose description of Greece is not wrong or distorted but simply does not coincide with Greece’s own image of itself.” This is a valuable point and part of Greece’s problem. But it is also fascinating to see how About gradually changes as the book develops. After honing his wit on the vanity and foibles of the Greeks he met in Athenian society and in the dusty new capital’s streets, after presenting a number of colorful foreign residents (most notably Sophie de Marbois-Lebrun, Duchess of Plaisance, and Jane Elizabeth Digby, or Ianthe, as one of the time’s most colorful women was known), About ventured into the anarchic countryside.

As his visit to the Peloponnese progresses, in the company of architect Charles Garnier and the painter Alfred de Curzon, About witnesses the combination of poverty and dignity of country people and begins to lose his mocking tone. He begins to understand the tribulations and the virtues of the Greeks. The last two chapters describe these encounters and provide much food for thought in the traveller’s mind with regard to the currents of history and the fate of people. “There will always be something inexplicable in the unquestioning love of the mountain dwellers for the soil that does not want to nourish them. The people of Greece’s mountains refuse to emigrate, and when they do decide to leave they want to return to their rocks,” About writes.

Early in the book, he predicts that in a hundred years there will no longer be any “pallikars,” the rough-and-ready warriors who stood in stark contrast with the dark-suited functionaries of the new state. “Today the whole Greek race is, in some way, divided into two nations, with the one absorbing the other. The future belongs to the men in black suits,” he predicts. At the end, leaving an Arcadian village, the hitherto haughty About says, “We had liked everything – the place and the people.” And the wine that the villagers had given them brought back fond memories of his own country, of the villages where “people laugh whole-heartedly and wake the Gaul who slumbers beneath the Frenchman’s black suit.”

He came to mock but About left a wiser man. Like so many other visitors through the ages. And Greece remains inscrutable.

About the author

Edmond Francois Valentin About was a French author, journalist and member of the Academy. He was born in 1828 and died in 1885. In 1852 he came to Athens on a French School scholarship and wrote about his two-year stay in “Contemporary Greece,” which was published in 1854. A year later he published “King of the Mountains,” the tale of a Greek highland robber who wants to be minister of justice. Both books raised vigorous protests at About’s portrayal of Greece and the Greeks.