Apostolos Kouroupakis

The Cyprus Museum, built in 1908–1909, has spent the past 117 years safeguarding some of the island’s most important archaeological finds, drawn from hundreds of excavation sites across Cyprus. For more than a century, on what was once Museum Street and, more recently, renamed Mikis Theodorakis Avenue, a decision by Nicosia’s municipal council that, in my view, disrupted the area’s fragile memory, generations of pioneering archaeologists left their mark here. Names such as Menelaos Markidis, Porphyrios Dikaios and Vassos Karageorghis are inseparable from this building.

The Cyprus Museum is, in many ways, the story of Cypriot archaeology itself, a museum within a museum. I come to understand this quickly as archaeologists Efthymia Alfa and Anna Satraki, who oversaw the museological curation and coordination of the upgrade of the permanent exhibition, generously share their work and thinking with me. Overall coordination was led by Eftychia Zachariou, Director of Antiquities.

The upgrade was carried out by the Department of Antiquities of the Deputy Ministry of Culture, in the context of Cyprus assuming the Presidency of the Council of the European Union in the first half of 2026.

Breathing New Life Into Old Walls

I meet Ms. Alfa at the museum entrance. She and her colleague will guide me through the refreshed galleries, which feel renewed without losing their soul. As we wait for Ms. Satraki, who is in the museum storerooms overseeing the careful packing of Cypriot antiquities set to travel to the Louvre, I ask what exactly happened over the past months, when visitor access to parts of the museum was restricted.

“We were asked to upgrade the museum’s galleries,” Ms. Alfa tells me, “and very quickly we realized this was anything but simple.”

The project became an opportunity to revisit the collections, prepare for the eventual move to the new Archaeological Museum of Cyprus, and rethink the museum’s existing spaces not just as containers of objects, but as exhibits in their own right. Even the old display cases, relics of mid-20th-century museum design, were treated as part of the museum’s history.

“Yes, it’s an upgrade,” she says, “but not in a way that makes the museum unrecognizable to those who know it.”

As we begin the tour, she explains that new narratives have been added to the permanent exhibition, including the Late Epipalaeolithic period, marking the earliest evidence of human presence on the island. The curators also took the chance to bring objects out of storage, reassess them, and, with the help of conservators, finally give exhibition space to finds that had long remained unseen.

A Museum in Transition

The challenges were many. The two archaeologists had to make decisions from scratch about re-displaying objects and introducing a fresh archaeological and museological approach, all while knowing that, once the new museum opens, the Cyprus Museum as we know it will eventually close.

As Ms. Alfa explains, they had to find solutions for objects whose future display in the new museum remains uncertain. “This is a transitional period,” she says. “And that reality shaped the way we approached the upgrade.”

Their aim was to preserve the feeling of a “museum within a museum.” They didn’t want to shut the doors while preparing for the move. Instead, they wanted to strengthen the visitor experience right now while quietly preparing for what comes next.

Ms. Satraki adds that the challenge was translating today’s scientific knowledge into an already structured museum environment, while respecting the work done by earlier generations. “It was a joy and an honor,” she says, “to work with objects discovered and studied by great archaeologists and to add our own layer of information.”

New Stories, Clearer Connections

In the newly updated Ceramics Hall, visitors can now more clearly see Cyprus’ connections with Syro-Palestine and Egypt. Short, accessible texts in Greek and English guide the visitor, and new educational programs for children are already planned, including one focused on animals (I was particularly taken by the Shillourokambos cat).

A key highlight of the renewed exhibition is the Chalcolithic period, which is almost being introduced anew to the public. Archaeological sites from western Cyprus, such as Erimi, Lemba and Souskiou, reshaped our understanding of this era in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The exhibition also re-examines the end of the Chalcolithic (around 2800–2500 BC), now seen as the beginning of new social and economic conditions, challenging older interpretations that placed major change later, in the Bronze Age.

Innovations of the Early and Middle Bronze Age are also highlighted: new burial practices, changes in cooking methods, intensified copper exploitation, and the rise of textile production.

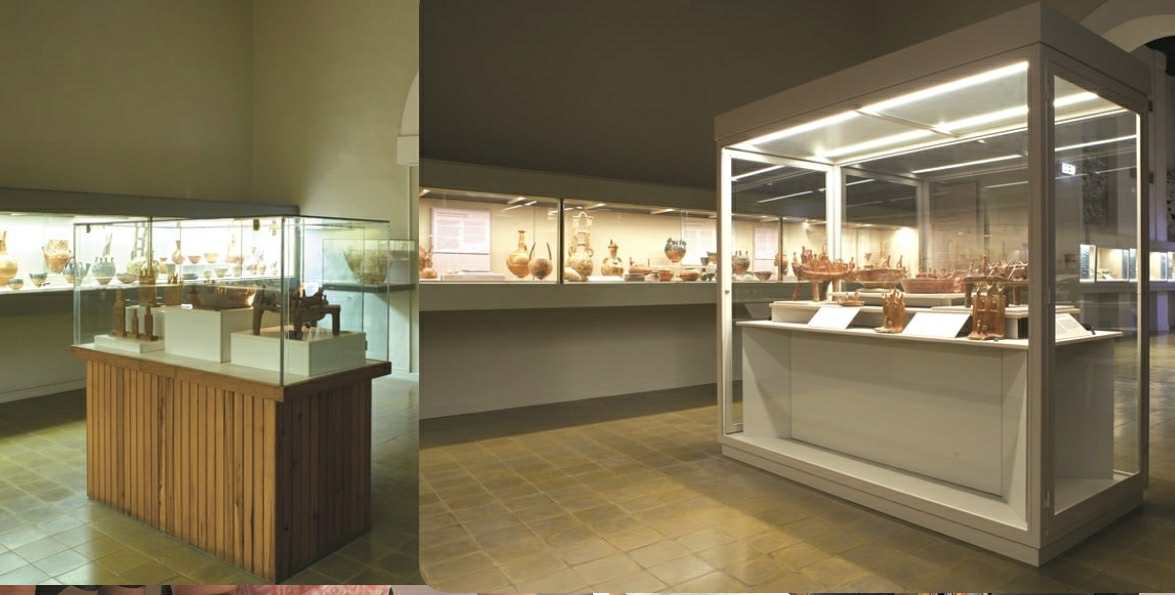

Hall 2 of the Museum, which hosts finds from the Early-Middle Bronze Age, before (left) and after (right). With the re-exhibition of the finds and the exhibition of new objects, the Cypriot history and its international ties are being reintroduced to the public.

Hall 2 of the Museum, which hosts finds from the Early-Middle Bronze Age, before (left) and after (right). With the re-exhibition of the finds and the exhibition of new objects, the Cypriot history and its international ties are being reintroduced to the public.

From Storerooms to Spotlights

Local variations in Cypriot pottery are now clearly presented, something visitors couldn’t easily see before. As Ms. Alfa explains, museology has evolved: objects once dismissed as “not beautiful” are now recognized for what they reveal.

Many objects from recent excavations across free Cyprus have been taken out of storage, conserved, and gradually introduced to public view. Ms. Alfa describes the process with unexpected tenderness, objects “resting on special cushions,” like infants, before moving to their next display. A small camel figurine from recent excavations in Latsia didn’t even make it into storage before being conserved and placed on display.

The exhibition also includes repatriated antiquities, reflecting the impact of colonialism and the rupture caused by the 1974 invasion on Cypriot archaeology.

As Ms. Satraki puts it, “Objects without historical context eventually become just art history.” Here, periods flow calmly into one another, helping visitors grasp the island’s long historical continuity and its international ties.

The entire Department of Antiquities worked tirelessly to upgrade the Permanent Collection of the Cyprus Museum. All the specialties of the Department bent over the findings with care.

The entire Department of Antiquities worked tirelessly to upgrade the Permanent Collection of the Cyprus Museum. All the specialties of the Department bent over the findings with care.

A Loving Farewell

By the end of my conversation, it’s clear that both archaeologists don’t just work at the Cyprus Museum; they love it. They approached the upgrade knowing that these objects belong to the people of Cyprus and carry the island’s long story.

What stayed with me most was something Ms. Alfa said early on:

“We wanted to say goodbye to this exhibition with love, to give people, for the few years it has left in this building, a reason to come, to enjoy it, and maybe even to challenge some old prejudices about this museum.”

The new Archaeological Museum of Cyprus is slowly rising in western Nicosia. But here, in the old building, the heart of Cypriot archaeology still beats, and thanks to this thoughtful upgrade, it will continue to do so with dignity in the years ahead.

*Read the Greek version here.