Source: Daily Mail

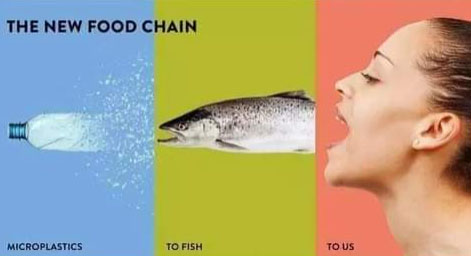

Microplastics – tiny pieces of plastic less than 0.2 of an inch (5mm) in diameter – have been found in human blood for the first time.

'We are already eating, drinking and breathing in plastic. It's in the deepest sea trench and on top of Mount Everest. And yet, plastic production is set to double by 2040.'

Scientists in the Netherlands took blood samples from 22 anonymous healthy adult donors and analyzed them for particles as small as 0.00002 of an inch.

The researchers found that 17 out of the 22 volunteers (77.2 per cent) had microplastics in their blood – a finding described as 'extremely concerning'.

Microplastics have been found in the brain, gut, placenta of unborn babies and feces of adults and infants, but never before from blood samples.

'Our study is the first indication that we have polymer particles in our blood – it's a breakthrough result,' study author Professor Dick Vethaak at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam in the Netherlands told the Guardian.

'But we have to extend the research and increase the sample sizes, the number of polymers assessed, etc.'

The study, published in the journal Environment International, tested for five types of plastic – polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), polyethylene (PE), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET).

Researchers found that 50 percent of the blood samples contained polyethylene terephthalate (PET). This was the most prevalent plastic type in the samples.

PET is a clear, strong and lightweight plastic that is widely used for packaging foods and beverages, especially convenience-sized soft drinks, juices and water.

Meanwhile, just over a third (36 percent) contained polystyrene, used in packaging and storage, while nearly a quarter (23 percent) contained polyethylene, from which plastic carrier bags are made.

Only one person (5 percent) had polymethyl methacrylate and no blood samples had polypropylene.

Alarmingly, the researchers found up to three different types of plastic in a single blood sample.

Differences between those who had microplastics in their blood and those who didn't may have been due to plastic exposure just before the blood samples were taken.

So, for example, one volunteer who tested positive for microplastics in their blood may have recently drunk from a plastic-lined coffee cup.

The health effects of ingesting microplastics are currently unclear, although a study last year claimed they can cause cell death and allergic reactions in humans.

According to another 2021 study, microplastics can cause intestinal inflammation, gut microbiome disturbances and other problems in non-human animals, and they may be causing inflammatory bowel disease in humans.

Yet another study published last year found microplastics can deform human cell membranes and affect their functioning.

More research needs to be done on their potential harm however, Professor Vethaak stressed.

'The big question is what is happening in our body?' he said. 'Are the particles retained in the body? Are they transported to certain organs, such as getting past the blood-brain barrier? And are these levels sufficiently high to trigger disease? We urgently need to fund further research so we can find out.'

The study was commissioned by Common Seas, a pressure group that drives for new policy to tackle plastic contamination.

'This finding is extremely concerning,' said Common Seas chief executive Jo Royle.

'We are already eating, drinking and breathing in plastic. It's in the deepest sea trench and on top of Mount Everest. And yet, plastic production is set to double by 2040.'

Dr. Fay Couceiro, Senior Research Fellow at the University of Portsmouth, said that previous attempts to measure microplastics in the blood have likely had contamination of samples through plastics in the air or from equipment.

'The paper is actually a method paper to show that it is possible to determine plastic in blood, and how to do it,' said Dr. Couceiro, who was not involved with the study.

'This research has taken a serious look at that issue and addressed it in a number of ways, by taking a large number of blank samples and including recovery data.

'Limitations to the paper are that it is only a sample from 22 people and there is no data on what exposure levels those individuals may have had.'

Dr. Couceiro said there's an 'urgency' to do more research in this area.

Dr. Alice Horton, an expert in contaminants at the National Oceanography Centre who was also not involved, called it 'a highly novel study'.

'Despite the low sample numbers and low concentrations detected, the analytical methods used are very robust and these data therefore unequivocally evidence the presence of microplastics and/or nanoplastics in blood samples,' Dr. Horton said.

'This is a concerning finding given that particles of this size have been demonstrated in the lab to cause inflammation and cell damage under experimental conditions.'

Members of the public who are worried about ingesting microplastics can take precautions, Professor Vethaak said.

These include opening windows in the home, as microplastic concentrations tend to be higher inside buildings than outdoors, and limiting the contact between plastics and the food we eat.

A 2019 study has already suggested that people unintentionally consume tens of thousands of these particles every year.

A WWF report, also published in 2019, suggested we're all unintentionally ingesting enough plastic to fill a cereal bowl (125 grams) every six months.

At this rate of consumption, we could be eating 2.5kg in plastic in the space of a decade, which is about the same as a standard lifebuoy.

Microplastics are also known to infiltrate the food we eat (including fresh seafood and fish fingers), water sources, the air and even in snow on Mount Everest.

It is estimated that, since the 1950s, more than 70 million tonnes of microplastics have been dumped into the oceans due to industrial manufacturing processes.