Apostolos Kouroupakis

Among many documents and other historical papers that ended up in my hands, there was also a wedding invitation from 1970, for a wedding celebrated on October 4 of that year, at the church of Prophet Zacharias in Pano Dikomo, at 4 p.m. I thought that it wouldn’t be of any real use to me. Surely, though, it would be precious to the couple who were beginning a shared life in Dikomo, now occupied, living between the borders of Pano and Kato Dikomo. I began searching immediately, with that hesitation that feels necessary. Are they alive, are they well… It required tact, but I felt strongly that it had to be delivered to its original recipients, to Dimitrakis and Irini, even fifty-five years later.

In the end, the search proved far easier than I expected; a single phone call to the community leader of Pano Dikomo, Mrs. Maria Tsiourtou, was enough for me to find Dimitris Konstantinou and Irini Venizelou of Kato and Pano Dikomo respectively; refugees now, living in one of the Strovolos settlements.

Mrs. Tsiourtou needed less than a few hours before calling me back: the couple had been found, and Mr. Dimitris would get in touch with me. And so he did; we arranged to meet on Monday afternoon. I wanted to confirm that Mrs. Irini would be present as well. “Will your wife be with us?” I asked. “Of course,” he replied, and we settled on a time.

On Monday afternoon, searching for their house number, I asked two women nearby; they showed me the home. “Are you also refugees?” I asked, almost intrusively. “Yes,” they answered. I insisted, as if I were seeking one more story: “Where are you from?” One answered, from Gerolakkos; the other, from Larnakas tis Lapithou. I wished them goodnight and continued toward the couple’s home, wondering what stories they might have told me. But at once I refocused on my task.

Soon I was ringing the bell of the refugee home of Dimitris and Irini Konstantinou. The house was decorated for Christmas; their welcome was warm, so warm, and I immediately felt I had done the right thing. This wedding invitation had to return to them. Without delay, after the first introductions, I handed the envelope to Mr. Dimitris. He opened it reverently and drew out the invitation; Mrs. Irini sat beside him, leaning in to read the text… I did not ask anything yet. This moment demanded silence.

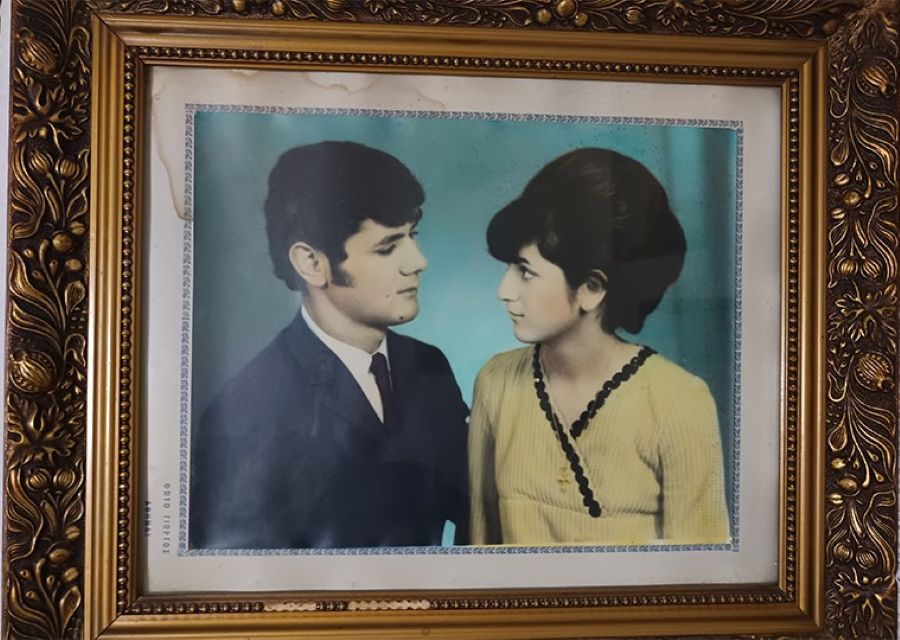

Fifty-five years later, a couple who had lived through a thousand upheavals returned to a time of innocence, hope, and dreams. I could see it in their eyes as they looked at it, years when the future was wholly their own. They look and look again at the invitation; Mr. Dimitris tries to recognize the handwriting of the name of the guest: “Now, which sister wrote this? I have two sisters who were teachers, and two more. One was a director at an insurance company, and the other moved to America after ’74,” he tells me. The two of them keep staring at the card; I gather courage and ask how they met.

“In the village,” Mr. Dimitris says. “In ’69. It was her brother’s engagement. He was a soldier with me. That’s where we met.” Mrs. Irini adds: “He saw me, I saw him, and that was it… one glance!” And as they recounted their first meeting, I noticed how that glance still lived between them.

They met on Easter 1969, were engaged that October, and on October 4, 1970, they married. “So many years… we’ve been together. We have four children, eight grandchildren, and four great-grandchildren,” Mrs. Irini says proudly, murmuring softly, “Ah, my goodness, my wedding invitation…” while Mr. Dimitris was already sending a photo of the invitation to the family group chat.

Congratulatory visits

I wanted them to bring me into the atmosphere of the days before the wedding, those days mentioned in the invitation when they would receive congratulations at their home in Dikomo: “Congratulatory visits will be received at their residence on Sunday and Monday in Dikomo.” I ask them, “Try to remember those wedding days. How did you make the invitations?”

Mr. Dimitris replies: “Her grandmother was the kaléstra of the village. She would go house to house with the invitation and a candle in her hands.” The grandmother was Chrystalla Venizelou, mother of Mrs. Irini’s father. “That’s how they invited people back then,” he adds.

Mrs. Irini continues: “On Saturday, there was a celebration at the bride’s mother’s house to ‘fill’ the bed. The bridesmaids would come to decorate it.” And Mr. Dimitris adds: “We married at Prophet Zacharias; we walked there…”

Mrs. Irini: “The ovens were full of food, the tables set, and whoever came greeted us and gave a pentosselino.” Mr. Dimitris explains that guests gave five shillings to each of them; the closer relatives gave more. On Monday, as stated in the invitation, the couple continued receiving guests: “Monday was the dance of the couple. We had to dance. People would pin the gold pounds and some wanted to give more. They’d pin the coins. Sometimes you could even make a whole chain!” Mrs. Irini says, emphatically repeating: “Those were proper weddings. They were very beautiful. Whoever came had to greet, to eat, to drink, to celebrate.”

“I’ll have it framed”

Today the church of Prophet Zacharias in Pano Dikomo, where Dimitrakis and Irini were married, no longer exists—it was demolished by the occupying army. The church, as they both tell me, was relatively small: “Not big like the ones they build now. A bit smaller than Agios Georgios of Kato Dikomo,” Mr. Dimitris says. “With its cypress trees, with its courtyard,” adds Mrs. Irini. “It was our church.”

The priest who performed the sacrament was Papa-Andreas, the village priest of Dikomo, originally from Bellapais—kin to Mr. Dimitris on his mother’s side. He was the last priest of Dikomo, Papandreas Ioannou, who died in 1986, far from the churches of Agios Georgios and Prophet Zacharias.

And just before we finished our conversation, looking again at the invitation, Mrs. Irini says once more: “Panayia mou, my invitation. I wanted this thing so much.” And again I thought how important a simple wedding invitation can be, and how many memories it can unlock.

Mr. Dimitris adds: “I’ll have it framed.”

Before the church, there had been the juniper-wood factory of Mrs. Irini’s father, Michail Venizelou. Mr. Dimitris’s father had been a horse-racing trainer since the 1950s… “The families of Savvas Konstantinou (of Kato Dikomo) and Michail Venizelou (of Pano Dikomo) invite you to the wedding of their children.”

I left their home overflowing with emotion; I felt as though I had feasted with them at their three-day wedding, as if I, too, had been invited into their joy. Now that I think of it, I owe the couple more than five shillings.

At our home

The couple’s house had been built by Mrs. Irini’s father, Michail Venizelou, almost on the border between Pano and Kato Dikomo. Before being given to the newlyweds, the building had been rented by the community and served as the school of Pano Dikomo, with two classrooms, for five or six years. The house, in honor of the wedding, was renovated, furnished, equipped; Mrs. Irini still remembers the glasswork… Her father, who owned a construction-materials plant, had covered the veranda in black marble. “It was beautiful,” they say. But by 1973 fashion had changed, and they changed the color of the veranda.

“I never enjoyed my house, not at all, since the dowry my parents made for me stayed there; jewelry, silver…” she says. Yet neither of them complains; they give thanks to God and are grateful for their home in Nicosia, which often fills with their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

“I lived in my house four years. I had two babies there. One was three years old and the other three months,” Mrs. Irini, originally with the maiden name Venizelou, tells me. Together, she and Mr. Dimitris, written as Dimitrakis on the invitation, lived between Pano and Kato Dikomo until July 1974, adding: “Whenever we go to Dikomo and return, and she sees her house, our house, she is ill for a week from the grief of it.”