Promotional Activity

Introduction

On 22 December 2025, the House of Representatives approved a wide-ranging tax reform package, with most measures taking effect from 1 January 2026. It is not an incremental adjustment. In my view, it is a deliberate recalibration of Cyprus’ fiscal model: targeted relief for households, a structural reset of dividend taxation, a higher corporate rate aligned with international direction, and—just as importantly—an unmistakable shift toward stronger enforcement and broader filing expectations.

What makes this reform particularly noteworthy is the balance it attempts to strike. Cyprus increases corporate income tax, but simultaneously lowers shareholder friction on post-2026 distributions and removes outdated deeming mechanics. It tightens real-estate-linked capital gains rules to address avoidance, yet abolishes stamp duty to reduce transactional drag. And while it modernises administration powers, it preserves core pillars (IP Box, NID, and the long-standing approach to securities) that remain central to Cyprus’ competitiveness.

This article reviews the Cyprus Tax Reform 2026, focusing on the measures adopted, the rules that remain unchanged, and the combined impact on private clients, owner-managed businesses and international structures.

- Individuals and families: higher tax-free threshold, revised brackets, and targeted allowances tied to household income

The reform’s first “signal” is social and economic: it increases the tax-free threshold and introduces clearly quantified allowances for families and household costs—yet it does so through explicit income tests, moving Cyprus toward a more targeted model of relief.

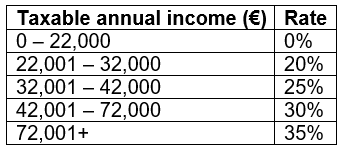

1.1. The new personal income tax scale (effective 1 January 2026)

The tax-free threshold increases to €22,000 and the brackets are re-shaped as follows:

This matters in practical payroll terms because it changes the effective tax burden for a broad middle-income segment, not only at the margin but across the annual profile of withholding.

1.2. The “family and household” allowances — and the income thresholds that control eligibility

A core feature of the reform is that the new allowances for children, housing costs and green expenditure are available only if annual income remains below specific thresholds, calculated by reference to household composition (number of children as at 31 December of the tax year).

Eligibility thresholds are as follows:

- Annual family income (spouses/cohabitees) less than €90,000 with no children

- Less than €100,000 where the number of children is one or two

- Less than €150,000 where the number of children is three or four

- Less than €200,000 where the number of children is five or more

- Single persons less than €40,000

Where the relevant threshold is met, the law provides that allowances are granted to each spouse or cohabitee (or to the single person, as applicable). This design is policy-significant: it aims to ensure the benefit is concentrated where it is intended—households that are carrying higher living costs and family obligations, but are not within the highest income tiers.

1.3. What exactly is allowed: the amounts and the categories

The reform introduces the following allowances (structured as deductions from taxable income):

(A) Children allowance (per spouse/cohabitee)

- €1,000 for the first dependent child

- €1,250 for the second dependent child

- €1,500 for the third dependent child and above

The reform also clarifies that “dependent children” include students up to the age of 24, which broadens applicability for households supporting children through tertiary education—often the costliest phase for family budgets.

(B) Housing allowance (per spouse/cohabitee)

A deduction of up to €2,000 is granted for:

- interest on a performing loan for the purchase of a primary residence, or

- rent for a primary residence

Two points deserve emphasis. First, this allowance is designed to be operationally straightforward: it targets two categories that represent the dominant housing cost for most households—loan interest or rent. Second, it reinforces a wider policy objective: supporting home ownership and long-term housing stability, while still recognising the reality that a large portion of the market rents its primary residence.

(C) Green transition allowance (per spouse/cohabitee)

A deduction of up to €1,000 is granted for:

- energy upgrading of a primary residence, or

- purchase of a new electric vehicle

This is a classic example of the reform’s “dual purpose” design: relief for household budgets that simultaneously nudges behavioural change and supports the wider green transition agenda.

(D) Home Insurance Allowance (per spouse/cohabitee)

A deduction of up to €500 is granted for home insurance against natural disasters. This provision reflects the broader policy objective of supporting household resilience in the face of climate-related risks and environmental volatility.

1.4. Other individual-level changes: clearer treatment of termination payments and expanded allowable deductions

Beyond the headline brackets and family allowances, Parliament passed additional changes that matter in employment and private client planning:

- The special regime for foreign pension income is modernised. Tax residents receiving pension income from abroad may choose annually to be taxed either at normal progressive rates or at a flat 5% rate on pension income exceeding €5,000 per year (previously €3,420). This adjustment recognises the changing composition of retirement income for internationally mobile individuals and reinforces Cyprus’ long-standing appeal as a European destination for pensioners and retirees.

- Ex gratia lump-sum payments (at the commencement or termination of employment) are clarified as subject to income tax at a flat 20%, after granting a tax-free amount of €200,000 in cases where the payment is made due to termination of employment. This is a material point for senior employee exit packages and negotiated terminations, where the tax outcome often determines commercial feasibility.

- The deduction from taxable income of individuals is extended to include insurance premiums for permanent or partial incapacity, in addition to life insurance. From a policy perspective, this supports personal resilience and risk planning—something Cyprus historically under-incentivised compared to some peer jurisdictions.

- Increased capital allowances of twenty percent (20%) are granted for expenditure incurred on machinery and installations used for agricultural or livestock production, after deducting any subsidy amounts.

- Dividends and SDC: the structural pivot — deeming ends for new profits, actual dividends become cheaper, and anti-avoidance is sharpened

If one had to identify the reform’s “centre of gravity” for business owners, it is here. Cyprus has reworked the mechanics of shareholder taxation in a way that is likely to influence corporate behaviour, investment decisions, and reinvestment patterns.

2.1. Deemed Dividend Distribution: abolished for profits earned after 1 January 2026

The reform abolishes deemed dividend distribution (DDD) on profits earned after 1 January 2026.

In practical terms, this is not a cosmetic change. For years, DDD created friction by imposing shareholder tax outcomes that did not necessarily reflect commercial reality—particularly in periods where companies retained profits for growth, working capital, debt reduction, or strategic investment. Moving away from deeming is, in my view, one of the reform’s most constructive features because it restores a basic principle: tax follows real distributions, not statutory assumptions.

2.2. SDC on actual dividends: reduced from 17% to 5% for post-2026 profits

For profits generated after 1 January 2026, the SDC rate on actual dividend distributions is reduced from 17% to 5%.

This reduction materially changes the tax “cost of extraction” for Cyprus tax residents who are within the SDC net. It also strengthens Cyprus’ narrative as a jurisdiction that rewards productive reinvestment: corporate tax rises, but shareholder-level friction on distributions of new profits falls, and the system becomes less dependent on deeming.

2.3. Concealed dividends (anti-avoidance): 10% SDC on hidden profit distributions

A new anti-avoidance rule introduces a 10% SDC charge on “concealed dividends” (i.e. value transfers to shareholders or connected persons that, in substance, represent profit distribution without being declared as dividends). This provision operates as a counter-balance to the abolition of deemed dividend distribution for post-2026 profits and reinforces the shift from deeming to substance-based enforcement.

2.4. Outbound dividends: 5% withholding tax to low-tax jurisdictions

The reform introduces a 5% withholding tax on dividends paid to a company resident in a jurisdiction with a low tax rate, as defined in the legislation.

This is a targeted anti-avoidance measure and, in practice, it elevates the importance of recipient-jurisdiction mapping and documentation. For groups using Cyprus as a holding platform, the message is clear: Cyprus remains internationally competitive, but it is no longer indifferent to “destination tax integrity” where low-tax recipient jurisdictions are involved.

2.5. Rental income and SDC: abolished (rental income remains within income tax)

The imposition of SDC on rental income is abolished (the well-known 3% on 75% mechanism). Rental income continues to be subject to income tax, but the SDC overlay is removed.

This improves coherence and reduces an additional layer of taxation that was often perceived as an administrative burden rather than a principled tax policy choice.

2.6. Other SDC changes: interest and simplification of payment

The withholding tax rate of SDC on interest from government bonds of another EU Member State and on deposits of the Health Insurance Fund is reduced to 3%.

The reform also simplifies payment of SDC on income from foreign dividends and interest (from two instalments to one) by tying payment to submission of the income tax return—an administrative simplification that matters in practice, especially for individuals with cross-border income streams.

The package also introduces further technical refinements on the SDC treatment of certain interest categories, aiming to simplify and align the rules for cross-border income reporting.

2.7. Non-domiciled individuals: alternative taxation method after 17 years

An alternative taxation method is introduced for non-domiciled individuals after completing 17 years in Cyprus, for a period of five plus five years, with payment of a €250,000 lump sum per five-year period.

This is a highly specialised provision, but it clearly reflects a broader theme: Cyprus is tightening long-term resident treatment and ensuring that the non-dom narrative remains structured, predictable, and administrable.

- Companies: corporate income tax rises to 15%, but Cyprus remains competitive — and the package modernises incentives and remuneration

3.1. Corporate income tax: increased from 12.5% to 15%

The corporate income tax rate increases to 15%.

Yes, this is a headline shift. However, it should be understood in context. Even at 15%, Cyprus continues to sit at the competitive end of corporate taxation within the European landscape, particularly when one considers the wider system architecture: dividend mechanics for post-2026 profits are materially improved; major structuring pillars (NID and IP Box) remain in place; and stamp duty is removed, improving transaction efficiency.

In my view, the more accurate framing is this: Cyprus is moving away from being “the lowest rate story” and toward being “the best overall system story”—competitive headline corporate tax, but with a coherent set of shareholder, substance, and incentive rules.

3.2. Loss carry-forward: extended from 5 to 7 years

The loss carry-forward period is extended from five years to seven years.

This is particularly important for businesses with longer investment cycles—technology development, scaling phases, capital-intensive projects, and group reorganisations where profitability is intentionally delayed in favour of growth.

3.3. R&D and productivity measures: extended and enhanced

The reform extends the 120% super-deduction for research and development expenditure on intangible assets until 2030.

This is a material signal for IP-driven and innovation-led businesses. It strengthens Cyprus’ ability to compete for genuine substance and real development activity, rather than purely passive holding structures.

The maximum limit of entertainment expenses deductible from taxable income is increased to €30,000 (from €17,086), which is not merely a “comfort” change; it reflects the commercial reality of business development and client acquisition in certain sectors.

3.4. Modern economy provisions: crypto-assets and employee stock options

Two measures deserve particular attention because they modernise Cyprus’ tax toolkit:

- A special method of taxation is introduced for profits arising from the disposal of crypto-assets, with a flat rate of 8%, with the ability to offset losses from disposal against profits within the same year.

- A special taxation regime of 8% is introduced on stock option rights under an approved employer share scheme, with statutory safeguards and caps (including limits linked to remuneration and a maximum benefit threshold over time).

Taken together, these provisions send a clear message: Cyprus wants to remain relevant to the modern economy—founders, executives, and internationally mobile talent—where equity participation and digital assets are increasingly central to real compensation and real investment activity.

- Capital Gains Tax and real estate-linked structures: higher exemptions, a wider perimeter for property-rich share disposals, and stronger administrative control

4.1. CGT lifetime exemptions: increased materially

Lifetime CGT exemptions are revised upward:

- General exemption increased from €17,086 to €30,000

- Agricultural land exemption increased from €25,629 to €50,000

- Primary residence exemption increased from €85,430 to €150,000

This is meaningful social policy, especially in a market where real estate values and household mobility patterns have changed substantially over the past decade.

4.2. Property-rich share disposals: the “indirect” threshold reduced to 20%

The definition of immovable property is amended so as to reduce the percentage subject to taxation and to include the disposal of shares in companies where the market value derives indirectly by 20% (instead of 50%) from immovable property in Cyprus.

This is one of the clearest anti-avoidance measures in the package. It directly targets structures where property value is effectively sold through shares rather than through a direct transfer of the immovable asset itself.

The reform also introduces a method for determining disposal proceeds in cases where a company’s market value is essentially represented by the market value of immovable property, ensuring that declared consideration can be adjusted by reference to other assets and liabilities.

4.3. Commissioner consent and compliance linkage

A provision is introduced whereby the Commissioner of Taxation may withhold consent to the transfer of immovable property where the disposer or the purchaser is not fully compliant with tax obligations (with foreclosures excluded). This is a powerful administrative lever and, in practice, will elevate tax compliance from a “back-office issue” to a transaction-critical condition precedent in certain property deals.

- Stamp duty: repealed — a genuine reduction of transactional friction

The Law relating to Stamp Duties is repealed.

In a jurisdiction where commercial documentation is a daily reality—financing, share transfers, shareholder arrangements, service contracts, corporate governance documentation—stamp duty has historically functioned as a procedural and psychological barrier as much as a cost. Its removal is a practical competitiveness measure. It reduces friction, accelerates deal execution, and improves the overall “ease of doing business” experience, particularly for cross-border parties who are used to streamlined documentation workflows.

- Assessment, Collection and enforcement: broader filing, electronic rent payments, stronger administrative powers

No serious tax reform is complete without administration reform. Cyprus has made it clear that the new framework expects a broader filing base and provides the Tax Department with stronger tools.

Key measures legislated as part of the package (with most measures taking effect from 1 January 2026) include:

- The gross income threshold for mandatory submission of audited accounts by individuals increases from €70,000 to €120,000.

- The deadline for submission of corporate tax returns is moved to 31 January of the second year following the tax year, and this date also applies to payment of corporate tax.

- Submission of income tax returns becomes mandatory for all individuals who are Cyprus tax residents aged 25 and above, regardless of whether they have taxable income. Mandatory submission of income tax returns by partnerships is also introduced.

- From 1 July 2026, payment of rent relating to immovable property in Cyprus exceeding €500 must be made through bank transfer (or other recognised traceable banking payment methods, such as bank cheque, as applicable under the implementing framework). Payments of €500 or less may continue to be settled in cash.

- The Commissioner is given power to suspend operation of a business and seal premises under specified patterns of non-compliance, including repeated non-filing or non-payment where the total amount due (including surcharges) exceeds specified thresholds, as well as invoice/receipt non-compliance.

Alongside the headline compliance measures, the Reform also includes additional administrative streamlining and procedural adjustments. These will matter in practice for dispute timelines, filings, and the Tax Department’s day-to-day enforcement workflow.

From a governance perspective, these are not “technicalities”. They are a clear shift toward enforcement and traceability. In my opinion, this is where the success of the reform will be measured in practice: in the consistency, proportionality, and predictability with which these powers are applied.

- What remained the same: the pillars Cyprus chose to preserve

A reform that changes everything often creates uncertainty. Cyprus did not take that route. It preserved several pillars that remain central to investor confidence and long-term planning.

7.1. The Cyprus IP Box regime remains in force

Cyprus retains the IP Box framework under the nexus approach. For technology, software, and IP-driven businesses, this remains a cornerstone. While every case requires a proper qualifying-IP and nexus analysis, the strategic message is clear: Cyprus continues to support real innovation and real development activity within a recognised and internationally aligned framework.

7.2. Notional Interest Deduction (NID) remains available

NID remains in place. This is a critical feature for equity-funded structures—holding companies, financing vehicles, and investment SPVs—because it supports capital structure planning and can materially influence effective tax outcomes. In a world where debt and equity choices are often driven by tax asymmetry, the continued availability of NID is a meaningful signal of continuity for sophisticated structuring.

7.3. No CGT on disposal of securities (as a general rule) — but the real estate-linked carve-out is now tighter

Cyprus continues, as a general principle, not to impose CGT on disposals of “securities”. What changes is not the principle itself, but the tightening of the real-estate-linked perimeter through the revised definition and indirect threshold. The message for investors is straightforward: Cyprus still offers a stable securities-based framework, but property-rich exits must be modelled carefully under the new rules.

7.4. The Non-Dom regime remains a cornerstone (with defined long-stay mechanics)

The Cyprus non-dom framework continues to operate as one of the jurisdiction’s flagship features for internationally mobile individuals. While the reform introduces a structured extension mechanism after long-term presence, the core proposition—predictability and planning clarity for eligible taxpayers—remains intact.

7.5. The 60-day and 183-day tax residency rules remain in place

Cyprus’ residence rules, including the widely used 60-day rule, remain unchanged. For relocation and cross-border planning, this continuity preserves one of Cyprus’ most distinctive advantages: a residence framework that is both practical and well understood by international advisers and taxpayers.

7.6. Participation exemption and “Cyprus holding company” fundamentals remain

The core holding-company mechanics that support Cyprus as a regional platform remain in force, including the participation exemption principles commonly relied upon in group structuring. This continuity matters in practice because it underpins Cyprus’ long-standing role in inbound investment, group reorganisations, and international holding models.

7.7. The 50% employment income exemption remains unchanged

For inbound talent and relocation-driven employment structures, the established 50% exemption framework remains unchanged, preserving a key element of Cyprus’ attractiveness for executives and high-skilled professionals.

Conclusion

In my view, the Cyprus Tax Reform 2026 is best understood as a strategic balancing act. Corporate income tax rises to 15%, but Cyprus remains competitive in the European landscape, particularly when one considers the full system: dividend taxation becomes materially more rational for post-2026 profits; deemed distribution is removed; stamp duty disappears; incentives for R&D and modern remuneration are reinforced; and cornerstone frameworks like IP Box and NID remain intact.

At the same time, Cyprus is clearly signalling that the era of “light-touch administration” is ending. Broader filing obligations, traceable payment requirements, and stronger enforcement powers mean that compliance discipline is now a core part of business strategy—not a year-end box-ticking exercise.

The reform can genuinely strengthen Cyprus’ position as a credible, competitive and modern EU jurisdiction—provided that the implementing guidance is clear and the administrative approach remains predictable and proportionate. For taxpayers, the right approach in 2026 is not simply to “react” to the changes, but to re-model profit pools (pre- and post-2026), re-design dividend policy, revisit property-rich holding structures, and ensure compliance systems are robust enough for the new environment.

Sergios Charalambous – Partner and Head of the Corporate and Tax Department at Philippou Law Firm