By Yianni Papadopoulou

It wasn't a matter of instinct, he didn't accidentally smell impending danger. The facts spoke for Alexandros Simioforidis and he could not ignore them. As head of the echelon of the Greek KYP in Kyrenia, Cyprus, he was tasked with intercepting and deciphering Turkish conversations and observing the movements of military units in Alexandretta and Mersini. In 1974, for at least three months he saw an unusual, escalating mobility. He recorded information signaling intensive landing exercises, revocations of permits, requests for supplies of campaign materials, mass transfers of ammunition and informed his superiors about the possibility of a Turkish invasion. He had warned them in a timely manner, but it was not heeded.

things could have turned out differently if the information he had gathered had been used. "Everything I was sending was clear as day, it didn't take an analyst to see what would come next"

"So much information that I was sending, what happened to it, did it get lost? Shouldn't they have taken advantage of them so that we wouldn't have this outcome?." This is what Mr. Simaioforidis, colonel e.a., still wonders today at the age of 87. "We were so aware, that not a branch or leaf was moved without us knowing about it. And then we became ignorant as if we knew nothing, and then the Turks came "suddenly". I felt betrayed."

These days he is in Rahes Fthiotida, where he usually stays in the summers. A resident of the village, a retired officer himself, has received instructions and is waiting for us outside the church of "Agios Charalambos" with his motorcycle to direct us through narrow streets to his neighbor's square. "It's mobile History, you're going to hear a lot," he says before saying goodbye. Stout and with a sharp, quick step, Alexandros Simeoforidis leads us to his living room. His narrative remains unchanged over time. He can talk without pauses, recalling dates and names of military units. Although almost half a century has passed since the Turkish invasion, every year, whenever July 20 approaches, he relives that turbulent period. "I'm in Cyprus mentally," he says.

Mr. Simaioforidis retired from the military in 1985. In 2020 he was honored by the Deputy Minister of National Defense, Alkiviadis Stefanis.

Mr. Simaioforidis retired from the military in 1985. In 2020 he was honored by the Deputy Minister of National Defense, Alkiviadis Stefanis.

He was born in Pentavryso, Kastoria, graduated from the Permanent Non-Commissioned Officers School and in 1960, after exams, he attended Turkish language courses for a year at the Foreign Language School of the Armed Forces. In 1963, the Central Intelligence Agency requested from the Army General Staff three unmarried, Turkish-educated officers to join its force. He was selected and placed in Didymoteicho in May 1964. Four years later he was sent to Kyrenia, Cyprus.

There he monitored, among others, the 6th army corps in Adana and the 39th division based in Alexandretta, Turkey. Every September this division carried out a landing exercise from Mersin to Antioch, in which one of its three regiments took part in the rotation. In April 1974, however, with a difference of a few days, all three regiments successively carried out landing exercises. "It was unusual," he observed.

There were other troubling signs. In June of the same year, all licenses to the Turkish army were suddenly revoked. Mr. Simaioforides says that a major from the 49th regiment was seen in Alexandretta, dozens of kilometers away from his post. "The governor heard about it and demanded his head on a table." He remembers a Turkish officer mapping the "Five Mile" coast, where the landing would take place, swimming in sea masks. As the head of the KYP echelon, he gave his superiors all this information. Recipients of this information was the General Staff of the National Guard, the Greek Cyprus Force, and the Greek Embassy, while copies also reached the Greek Cypriot Office in Athens. "Our people knew that the Turkish army had been on alert since April," he says.

Developments accelerated after the coup on July 15, 1974. Two days later, an emergency meeting of Turkish senior officers was held in Mersin, where 16 landing craft were stationed. What followed was the "descent of the Myria", as described by Mr. Simaioforidis. A partial mobilization of 5,000 men was ordered to fill gaps in the units – something not usual in peacetime – while the engineer battalion commander was ordered to uproot all the trees on the shores of Mersin to prepare the area to receive the forces.

There was a "climax of preparations" on the opposite side. Reconnaissance flights were made over Cyprus, while warehouses of ammunition of various calibers were gradually emptied and transported to the coasts by registered trucks. Mr. Simaioforides remembers a Turkish signal that said all vehicles had to be emptied of fuel and soldiers had to wear long-sleeved uniforms because they would be crawling across the field. Under normal circumstances, he sent his superiors one or two informational signals every 24 hours. But he remembers that turbulent period of sending 17 to 18 a day. "I got no answer, no instructions," he says. "As if they knew it all and needed no further briefing." He followed the course taken by the Turkish convoy towards Cyprus and remained optimistic until the last moment. He thought there would be a reaction. "We of the echelon were rubbing our hands. The Turks will suffer a blow that they will remember for years, we used to say," he recalls.

The same as July 20, 1974, when he saw the Turkish fleet outside Kyrenia. It struck him that the personnel were on the decks, they seemed relaxed, without having taken any special safety measures, as if they were going for an inspection after an exercise. No organized preventive defensive measure had been taken on the "Five Mile" coast. He would later call the Turkish military operation a "disembarkation", not a landing.

"There wasn't a spark anywhere that wasn't on fire"

With the Turkish fleet opposite, the head of the KYP echelon in Kyrenia was instructed by Athens to advance as close as possible to the landing site and to inform the operations office in Greece of all developments. He expected six Phantom aircraft and two submarines to arrive and would need coordinates from him to strike Turkish targets. They never arrived. With no other means of direct communication available at the time, he took an 800-meter-long reel, connected the telephone to it, climbed a three-story building closer to the beach, and broadcast what vehicles the tanker "Erkin" was unloading. The cable did not reach the roof of the building and a colleague was on the ground holding the phone.

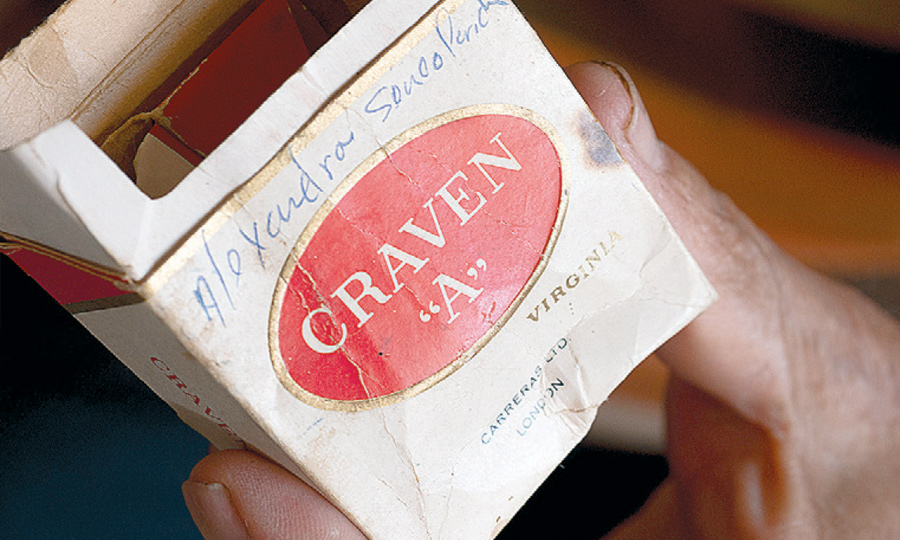

Souvenir of captivity. The pack of cigarettes that Alexandros Simioforidis had on him when he was imprisoned by the Turks.

Souvenir of captivity. The pack of cigarettes that Alexandros Simioforidis had on him when he was imprisoned by the Turks.

"With binoculars, but also with the naked eye, you cannot describe, no matter how good you are with the pen, the theater, the atmosphere. There wasn't a spot that wasn't on fire or bombarded. Hell! When you live the atmosphere, you don't think about the risk of being killed, it's like getting drunk", he said about those hours in October 1986 in his testimony to the inquiry committee of the Greek Parliament on the "Cyprus File".

At the time he was relaying everything that was happening, he was asked by the operations office if he could calculate where the Erkin's waterline was before the landing began and where it was now. The waterline, or load line, corresponds to the maximum permissible draft of a ship. "That's when I started cursing gods and demons," says Mr. Simaioforidis. The technical question he received at the critical moment of the invasion seemed out of place. "They didn't want to, they didn't want to. What were they interested in, the waterline or where the vehicles are?'' he says.

The controversy was observed during other times as well. He says he had seen 72 Turkish helicopters flying over him and the answer he received from Athens was that he did not know how to count and that Turkey had no more than 30 to 35 helicopters.

He remembers during the landing hours a Turkish tank running over a soldier and next to him another one leveling a car. Any resistance he observed in those hours was isolated and rudimentary. "Individual heroes," he comments. He was forced to retreat, the Turkish tanks now approaching menacingly. He was eventually captured and imprisoned for 17 days.

The tracks and the captivity

After observing the possible negative turn of events, he had already taken care to set fire to archival documents he kept in the KYP echelon. He had also thrown some machinery into two wells and destroyed others. He had to eliminate every trace that would betray his activity. If he was caught with all this material he considered his death sentence certain.

While he was in custody he remembers the interrogations, the sunless cell where he was placed and the little amount of food they were given. A piece of bread like the church offering and three olives was breakfast, a chicken wing cut in three with some spaghetti was lunch and nothing else after that. Hee lost nine pounds in two weeks. He thought he would be executed. Until one day he was hopelessly led to freedom, after an exchange of prisoners. "Can you imagine being freed after being condemned for execution? How does a person hold up?” he says. To this day he keeps in his file a crumpled packet of British Craven A cigarettes, which he had on him when he was caught and was returned to him shortly before he was released.

He continued to serve in Cyprus until 1978 and was later posted to the consulate general in Istanbul for four years, as consular harbormaster and assistant commercial attaché. He retired in 1985. He believes that things could have turned out differently if the large amount of informative material he had gathered had been used. "Everything I was sending was blear as day, it didn't take an analyst to be able to see what would come next," he said.

[This article was translated from its Greek original]