Newsroom

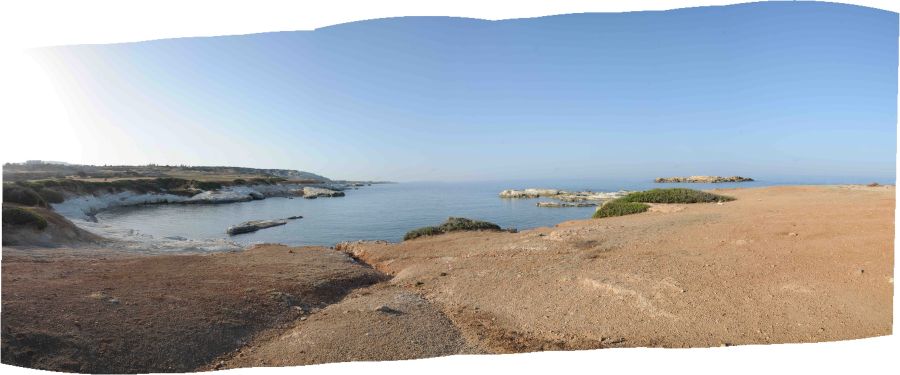

Archaeologists working along the rugged coast of Akamas have uncovered new evidence of Cyprus’ role as a vital maritime and religious hub during antiquity, following the completion of the 2025 excavation season at Agios Georgios, Pegeia.

The Department of Antiquities announced this week that a six-week archaeological mission led by New York University has concluded work at the ancient harbor of Maniki and the nearby Pegeia–Meletis necropolis. The project was directed by Joan Breton Connelly, professor of classics at NYU, in collaboration with scholars from the University of Cyprus and the Cyprus Institute.

At Maniki, archaeologists focused on the remains of an ancient harbor carved into steep coastal bedrock. More than 700 kilograms of Late Roman amphora fragments were recovered and studied under the supervision of Stella Demesticha of the University of Cyprus. Most of the vessels date to the 6th century A.D. and include locally made Paphian amphorae, alongside imports from Cilicia and the eastern Mediterranean, including Gaza.

Researchers identified 68 red-painted inscriptions on the amphorae, known as dipinti, a rare and largely understudied feature in Cyprus for this period. Scholars believe the broken vessels were deliberately dumped as construction fill, used to level the rocky shoreline so that piers and harbor installations could be built.

Those harbor works, archaeologists say, played a crucial role in supplying Cape Drepanum with massive quantities of Proconnesian marble during the reign of Emperor Justinian. The marble was used in the construction of monumental basilicas, underscoring the region’s importance during the Late Roman and early Byzantine era.

Inland, researchers continued work on a rock-cut tomb discovered in 2018, which was used from the Hellenistic period through late antiquity. Despite repeated looting over the centuries, the tomb yielded valuable ceramic, glass and metal finds. Pottery analysis shows continuous use from the 1st century B.C. to the 5th century A.D., while glass vessels include finely made bowls, beakers and bottles from the Roman Imperial period.

Scientific analysis is now underway on metal artifacts recovered from the tomb, with specialists using advanced techniques such as X-ray fluorescence to determine their composition. Human skeletal remains are also being studied, alongside animal bones that suggest ritual activity. Burnt remains of sheep, goats, pigs, fish and birds point to funerary offerings or meals shared by the living in honor of the dead, practices well known across the ancient Mediterranean.

The season also included extensive surface survey work at the Meletis necropolis and across fields surrounding the ancient harbor. Researchers documented tombs, artifacts and landscape features, while also recording oral histories from Pegeia fishermen who worked out of Maniki harbor in living memory.

Adding a historical dimension to the work, the team retraced parts of the 19th-century journey of British archaeologist David George Hogarth, following descriptions from his 1889 publication Devia Cypria. The effort connected modern archaeological research with some of the earliest explorations of Cyprus’ ancient past.

Officials said the findings once again prove the island’s long-standing role as a crossroads of trade, ritual and daily life, a story written not only in grand monuments, but also in broken pottery and humble tombs.