By Andreas Kadjikyriacou*

On November 30, 1963, just eight days after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, President Archbishop Makarios submitted to Vice President Dr. Fazil Kiouchuk the 13 points for improving the Constitution of the Republic of Cyprus. Turkey rejected the proposals, the Turkish Cypriots withdrew from the government, the atmosphere became charged and on the first occasion, during the Christmas period of 1963, bloody clashes broke out between Greek and Turkish Cypriots.

Kennedy's successor, Lyndon Johnson, had not completed three months in the Oval Office when he consented to Secretary of State George Ball's peacekeeping mission to the region to defuse the situation in order to prevent the possibility of a Greek-Turkish conflict. Ball was expected in Nicosia on 11 February 1964.

The Lyssarides team

A week earlier, at 8:30 p.m. on 4 February 1964, two explosions caused property damage to the American Embassy, while two American cars were set on fire elsewhere in Nicosia. British intelligence informed the CIA station in Cyprus that Lyssarides' group was behind the attack, noting that he was Makarios' "personal physician". The two bombers "of the Lyssarides groups" were named by a Cypriot Army official according to a document submitted to the Cyprus File Commission. However, it is unknown whether the bombs were planted on instructions or were known to Makarios, despite the widespread impression that nothing was going on in Cyprus that Makarios was not aware of.

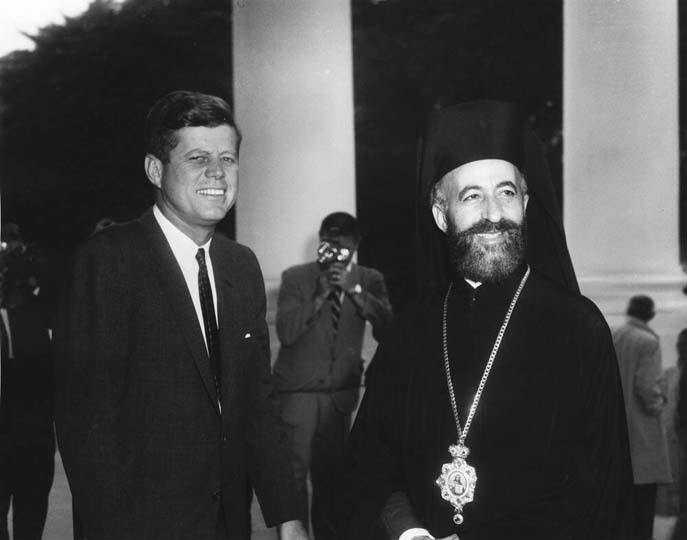

But why would Makarios or the Lyssarides group, acting as an arm of the Cypriot president, seek a confrontation with the US? At that time, especially at the time, when Makarios' relations with the US were perhaps at their best. In June 1962, John F. Kennedy received the Cypriot president at the White House, and three months later Vice President Johnson made an official visit to Cyprus. Makarios had also tacitly consented to the continued operation of the American radio monitoring station (FBIS) of the wider Middle East region in Karavas, and the top-secret National Security Council relay station in Gerolakkos.

The motive

So what was the motive behind the bombs? Because of the intercommunal unrest, the British, Greek and Turkish military detachments in Cyprus formed a joint force to end the fighting. The US pushed for the formation of a peacekeeping force for Cyprus with troops exclusively from NATO countries. The three guarantor powers and the Turkish Cypriots agreed, but "Archbishop Makarios felt he could not agree to this plan. Although he accepted in principle the need for an international force, he insisted that it should be under the direct control of the United Nations," according to British Colonial Affairs Minister Duncan Sandys. The bombs were intended to send a message against US plans. In June 1962, the Cypriot president was received by John F. Kennedy at the White House, and three months later Vice President Johnson made an official visit to Cyprus.

In June 1962, the Cypriot president was received by John F. Kennedy at the White House, and three months later Vice President Johnson made an official visit to Cyprus.

The Americans clearly suspected that Makarios was behind the anti-American climate being created in Cyprus. The embassy statement was sharply critical of him personally. "During the last few weeks, a systematic campaign has been waged against us in the Greek Cypriot press. We protested to the Government of Cyprus, but the campaign has continued and has now taken a new form," the embassy statement said. The US ambassador to Cyprus at the time was Fraser Wilkins, who was convinced that Makarios was aware "and I asked him many times to stop it. But he never did anything about it. He always avoided the subject, in a Byzantine way."

The anti-American sentiment was maintained after the bombing. The newspaper "Battle", published by Nikos Samson, who, like Lyssarides, maintained his own private army, implied from the very first moment that the bombing was staged by the Americans themselves. A caption under a photograph of a stack of boxes read that "ten hours before the explosions at the American embassy, the above boxes were sent to the American homes in Nicosia for the purpose of placing utensils and moving" ("Battle", 6 February 1964, p. 4).

Battle positions

Wilkins was at home with his family at the time of the explosion. The embassy residence was part of the embassy complex, located in the area near the former Hilton Hotel, which was not yet operational. As soon as he realized what had happened, he rushed his family and, accompanied by armed marines, rushed to the Presidential Palace for safety, but found only Presidential Guard officers on guard duty. Makarios was not there, but in the Archdiocese, where he was staying and from where he went directly to the embassy as soon as he was informed of the event ("Eleftheria", 5 February 1964, pp. 1 and 8).

Armed marines were deployed on the perimeter of the embassy ready to repel a possible attack and later British armoured cars were added, while the Cypriot police were in a state of confusion, trying to investigate the case.

Three chartered Pan-American flights were to take the Americans to the safety of Beirut and Mr and Mrs Wilkins said goodbye to each of the 700 women and children as they departed.

Three chartered Pan-American flights were to take the Americans to the safety of Beirut and Mr and Mrs Wilkins said goodbye to each of the 700 women and children as they departed.

The evacuation plan

The incident had collateral damage. According to the Consul General at the time, Charles McCaskill, upon his return to the embassy Wilkins called a meeting and decided to implement the plan to evacuate women and children from Cyprus. "It was a controversial move, but he announced it on Cypriot TV the afternoon after the bomb went off and he couldn't back down," McCaskill claims. "I had to evacuate 1,200 of the 2,000 Americans on the island," recalls Wilkins, who explains that "we had an unusually large embassy there, about 500 people in total, 35 of whom were embassy staff. The rest were all secret communications under the NSC [National Security Council] and FBIS, and so on."

The next day, Wilkins was standing with his wife on the aircraft ladder at Nicosia Airport, which in 1964 was still run by the Royal Air Force of Britain. Three chartered Pan-American flights were to take the Americans to the safety of Beirut and the Wilkins couple said goodbye to each of the 700 women and children who departed.

However, a week later, when Ball arrived on the island, "not all of the Embassy wives had left and I heard that [the US Secretary of State] was furious that some were still there. He gave the remaining dependents only a few days to leave" and arranged for Wilkins to be replaced. "Apparently [Ball] decided that the problem required a change of ambassador," according to McCaskill. Wilkins, who had mishandled the evacuation, couldn't handle the pressure and "started drinking too much," according to George McFarland, consul and political adviser to the embassy in 1964.

However, a year later Wilkins' name was implicated in reports of espionage in the Cypriot newspaper Agony. A New York Times article on the espionage issue included a statement by an embassy spokesman that "allegations that Americans have been involved in activities hostile to the interests of the Government, of Cyprus are patently false" ("The New York Times," March 6, 1965).

*ahadjikyriacos@gnora.com

SOURCES

- The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project CONSUL GENERAL CHARLES W. McCASKILL.

- The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Foreign Affairs Series GEORGE MCFARLAND.

- The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project Foreign Affairs Series FRASER WILKINS.Lefteris Papadopoulos, My testimony before the Ad Hoc Committee of the Cyprus Parliament on the "Cyprus File": traitors and betrayals against my homeland, sweet Cyprus (Nicosia: [n.d.], 2010).