By Demetris Rigopoulos

On Friday, July 19, 1974, 30-year-old Cyprus Airways pilot Adamos Marneros paced nervously in his London hotel room. British news networks, particularly the BBC, were continuously broadcasting updates on Turkey's imminent invasion of Cyprus, just four days after the Greek junta’s coup against President Makarios.

Marneros had more than just his family, home, and country on his mind. He was scheduled to pilot a Cyprus Airways flight from London to Nicosia, with a stopover in Rome that evening. Nicosia’s International Airport, temporarily closed after the coup, had reopened under pressure from foreign diplomats on Athens' envoy, Nikos Samson, to facilitate the evacuation of foreign nationals from the island.

This flight would be one of the least commercially viable in Cyprus Airways' history—just seven passengers were booked from London (a family of four Greek Cypriots and a family of three Turkish Cypriots), and none from Rome. Marneros, however, saw Rome as a strategic stop; he hoped to claim a technical issue that would allow them to delay the journey to Cyprus as the threat of Turkish invasion loomed. But Italian authorities gave the green light, and he was forced to continue the journey to Nicosia.

Marneros was concerned not only for the safety of his passengers and crew—two co-pilots and three flight attendants—but also because his plane was the only one of Cyprus Airways’ small fleet stationed outside of Cyprus. Should a full-scale conflict erupt, he feared it might be the airline’s only surviving aircraft.

Despite Marneros' efforts to persuade Cyprus Airways’ general manager to cancel the flight, CY317 was cleared to proceed. The flight took off just after midnight, early on Saturday, July 20, a date that would be forever etched in Cyprus’s history. Shortly after takeoff, Marneros contacted Athens’ Elliniko control tower, seeking news from Cyprus. Information was scarce, and a direct communication line to Nicosia couldn’t be established.

However, he received word that Nicosia’s International Airport was under occupation by EOKA B, the Greek-Cypriot nationalist militia that had played a key role in the recent coup.

Flying over the Aegean Sea, Marneros sensed the weight of the mission. “There was nothing in the skies, probably due to the time and the events unfolding. It felt eerily calm,” he recalls. Near Rhodes, as he set the aircraft’s radar toward the Turkish coast, the screen showed a significant dot near Antalya and three smaller dots—heading straight toward Cyprus. Alarmed, Marneros contacted Nicosia’s control center but was told to continue as planned. However, as they neared Cyprus’s coastline off Paphos, he noticed more signals—six large dots on the radar, an indication of something ominous.

With permission, he adjusted the flight path to circle Cyprus at an altitude of 15,000 feet, avoiding a direct approach. As they turned over Kyrenia, the radar confirmed what he feared: the Turkish fleet was advancing towards the island, with 21 ships visible on the radar. His homeland was surrounded.

Marneros safely landed in Nicosia at 4:10 a.m. He and the passengers quickly left the airport—one of the only vehicles moving through the eerily quiet streets at that hour. Moments later, as he neared the city, he saw Turkish transport aircraft escorted by F-104 fighters, followed by a swarm of paratroopers. Stunned, Marneros decided to drive home, barely avoiding bombs that narrowly missed his vehicle.

After the landing, a small group had maneuvered the plane to the middle of the runway in an attempt to block the Turkish aircraft from landing, though the Turkish forces ultimately had no need for Nicosia’s airport. Later that morning, the aircraft was bombed and remains there today—its debris a haunting reminder of that day. Reflecting on the momentous events of July 20, Marneros says, “Had we been even an hour late, I’m not sure where we’d be now.”

The abandoned Nicosia International Airport

Photographer Andros Efstathiou, born the year of the invasion, had no personal memories of the event, nor did his family become refugees. Yet he felt compelled to chronicle the "last flight" in a photo project capturing the abandoned remains of Nicosia’s airport, now under United Nations control within Cyprus’s buffer zone.

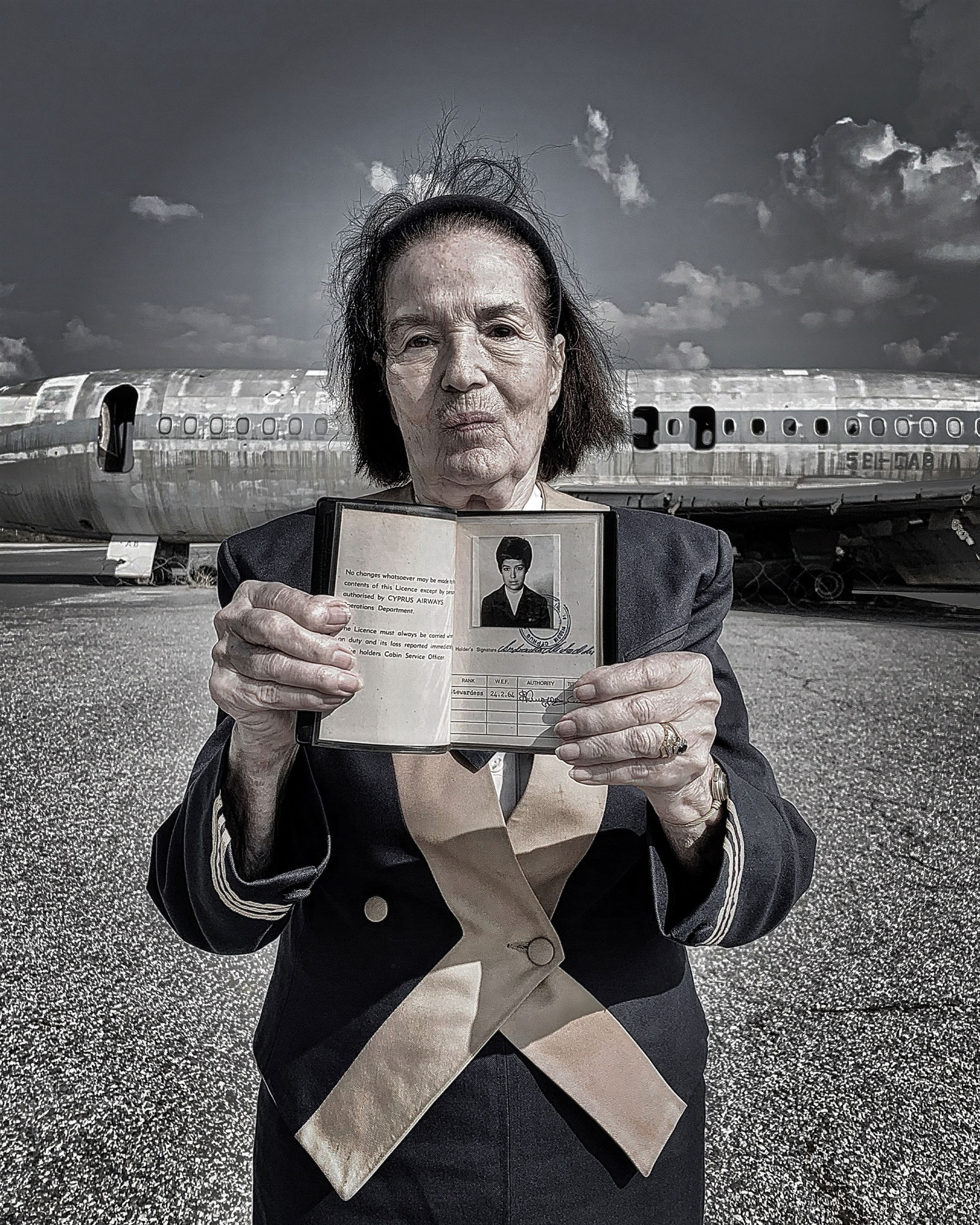

His journey began in 2006 while covering intercommunal talks at an airport outbuilding. Enchanted by the structure, Efstathiou began photographing it in 2007, sneaking inside when security guards recognized him and turned a blind eye. After years of covert visits, he encountered a former Cyprus Airways flight attendant from the pre-invasion era, inspiring him to locate others who had worked there on that final flight.

Eventually, enough staff members were found, each preserving their uniforms from those years. With special permission for a one-day shoot, Efstathiou produced a photo series featuring the airport and its former employees, immortalizing the building’s history and their memories.

Efstathiou’s project has since toured both Cyprus and abroad, with a part now held by the Thessaloniki Museum of Photography. In December, his work will be featured at Nicosia’s isnotgallery as part of the 50th-anniversary commemorations of the Turkish invasion.