Opinion

by Evanthis Hatzivassiliou

On August 3, 1977, Hellenism was struck by a tragedy of unspeakable magnitude: the president of the Republic of Cyprus, Archbishop Makarios III, passed away of a heart attack. His death occurred at a particularly critical time, amid ongoing discussions for the reunification of Cyprus based on an agreement recently signed by Turkish-Cypriot leader Rauf Denktas. The implementation of the necessary but odious compromises required became a much harder task without the unquestionable leader of the Greek-Cypriot community. Additionally, the Republic of Cyprus, having lost the man who led it to independence and had governed the country since 1960, was suddenly asked to transcend from the rule of a national leader to a different, significantly more demanding level of institutional and political organization. The historiography and public discourse have not highlighted enough what an achievement it was for the Republic of Cyprus to succeed in creating an exemplary Western democracy capable of European Union accession, despite reeling from such a great loss and the terrifying trauma of the invasion and occupation.

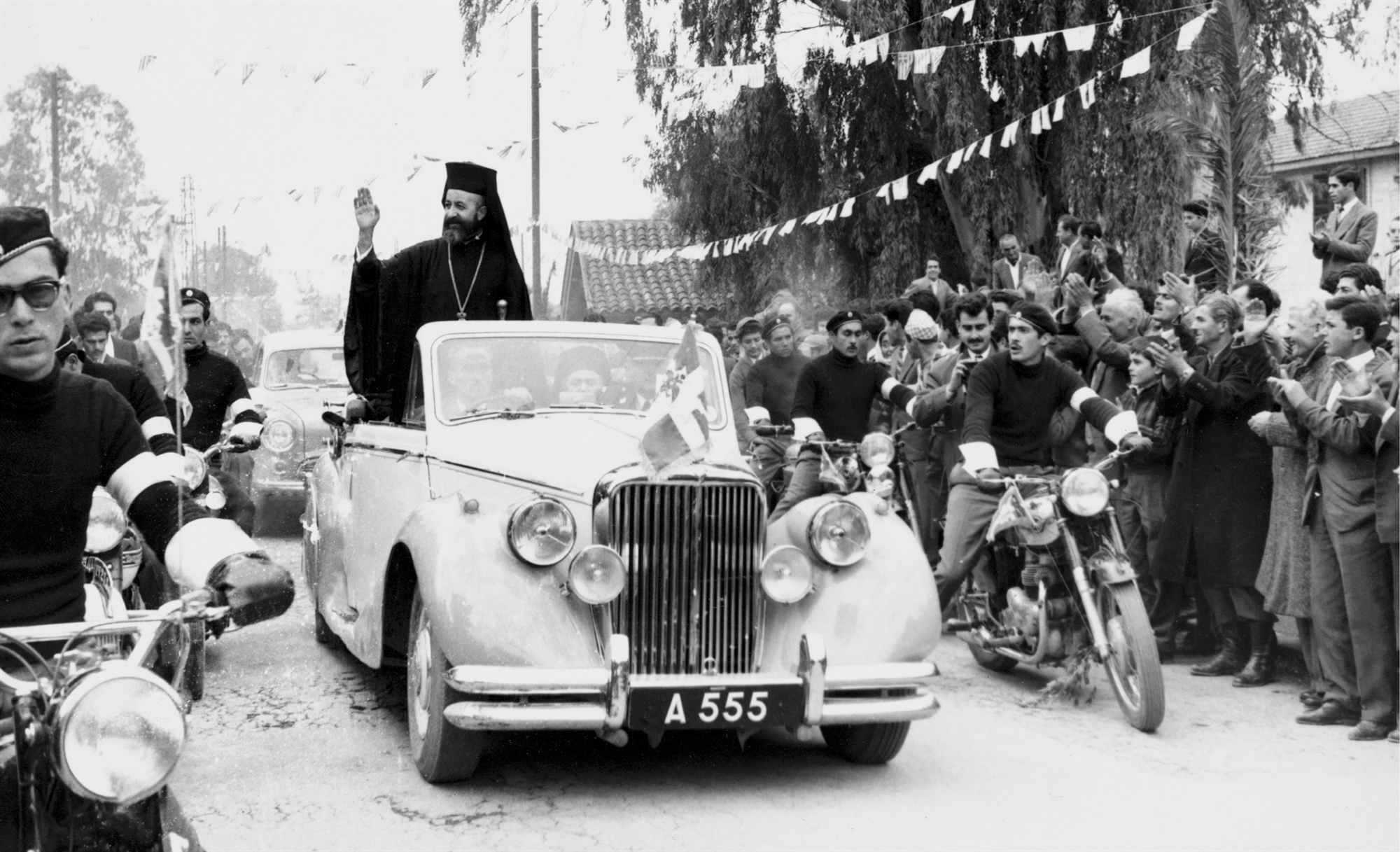

The last ethnarch

Elected archbishop by popular vote in 1950, Makarios III was the last ethnarch (in the original, politico-religious meaning of the word) in Greek history: He was not only the religious leader of his community, but he was also its political leader, the guarantor of Greek tradition and identity on the island. He threw himself with great gusto into the effort of unification with Greece. In “The Cult of Makarios,” the leading academic on British colonial history, Robert Holland, notes the awe the archbishop inspired in his British opponents in the 1950s, as the manifestation of a tradition stretching back 1,500 years. His great mental faculties were reinforced by this tradition, which he was both a part of and a focal point for, accompanied by his calm, charming and tremendously headstrong stance on the pressing national issue.

...the greatest mistake Makarios made...inducting Cyprus into the Non-Aligned Movement...A Turkish invasion of a Western member-state was inconceivable...an invasion of a non-aligned country was not.

His function as ethnarch always defined his position. Clearly, he was not a conventional political leader. As the ethnarch of Cyprus, he was always obliged to seek the widest possible convergence of interests and express the vast majority of his people. However, this is almost impossible for a leader who must also make difficult decisions that often lead to rifts, often painful ones. In other words, his role as ethnarch, in which he was assured widespread popular support and in the 1950s was empowered to pursue a goal that was both irredentist and anti-colonial in an exemplary way, limited him in one important way. He was unable to accept difficult compromises, whether in negotiations with Cyprus Governor John Harding in 1956 or even after independence, as this would cause a rift with a section of the island’s populace. This first became clear during the London and Zurich Agreements, which he accepted (and whose basic tenets were shaped by his instructions) despite the difficult provision of forever repudiating unification with the Greek mainland. It had to look like it was being forced upon him, and this is what he tried (and succeeded) to project. However, we should not forget that for this acceptance he was inundated by distressing accusations of being a “perjurer.”

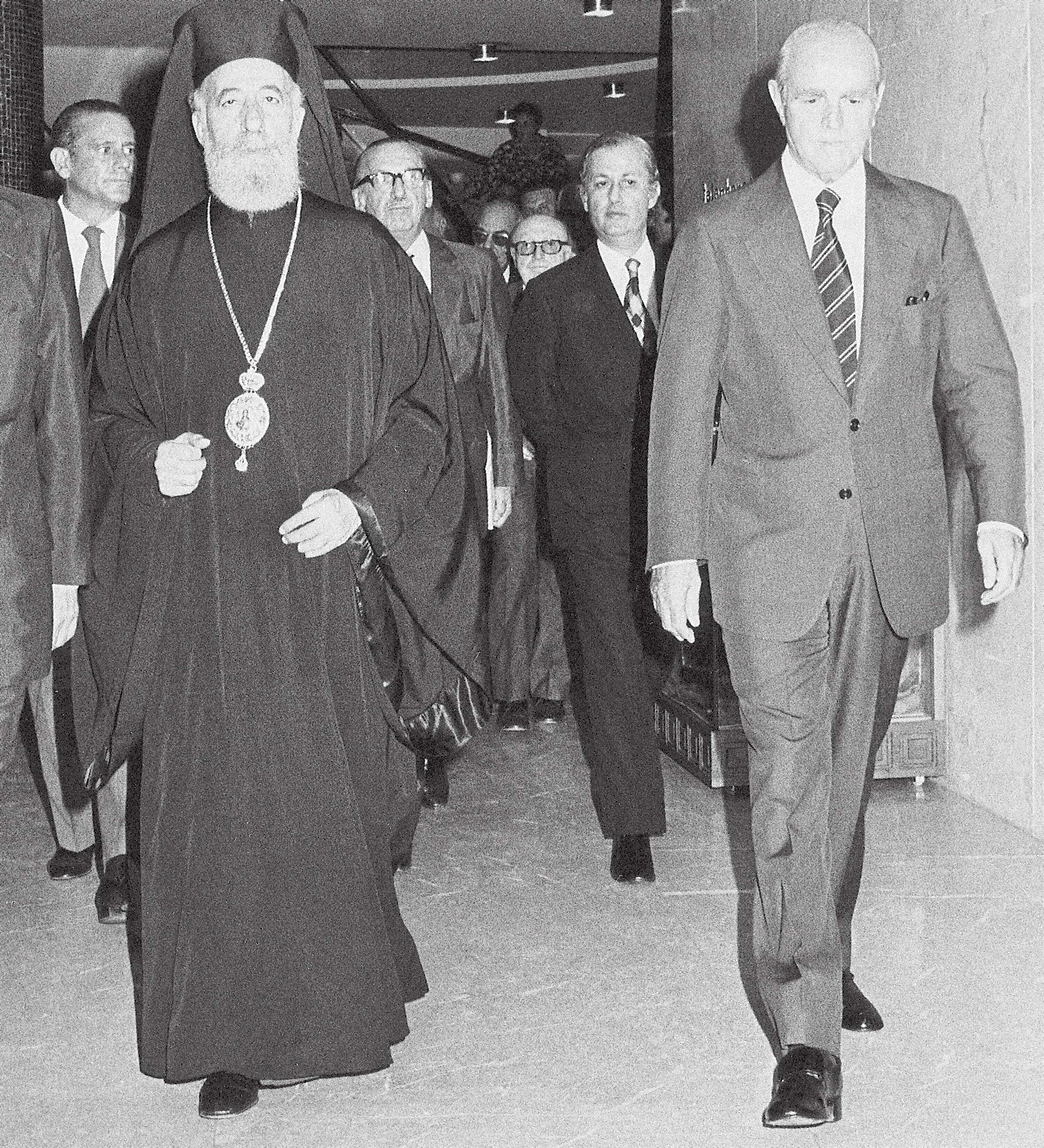

As the ethnarch of Cyprus, Makarios came into conflict with every Greek government he worked with. It has been pointed out, rather accurately, that he even clashed with the provisional governments. Nevertheless, he had a better relationship with – and more trust in – the governments of Konstantinos Karamanlis, which respected Nicosia’s independence as a decision-making center. On the other hand, his relations with the centrist governments, whether in 1950-52 or (particularly) 1963-66, were strained, specifically because they pursued a “national center” doctrine and were willing to trample on Nicosia’s autonomy. Centrist leaders, particularly in 1964-65, had better relations with his archrival, Georgios Grivas, with Georgios Papandreou even raising him to the office of supreme military commander of Cyprus in 1964, leading to the archbishop feeling a significant sense of insecurity and consternation (and reasonably so).

It was not part of his role as ethnarch, but it must not be forgotten that in the years 1967-74 Makarios also served a different function. He was the only elected representative of Hellenism, a counterpoint to the humiliating dictatorship in Athens. Maybe this was his finest hour, as he was the manifestation of a transnational demand for democracy. In fact, this was one of the reasons that led Dimitrios Ioannidis to attempt the catastrophic coup against the archbishop in 1974.

Dangerous maneuvers

As the leader of the unification effort, Makarios was the first Greek leader who said that we belong, or at least that Cyprus belongs, to the West, during an interview in London in 1953. However, his later choices departed from this statement, from his participation in the Afro-Asian Conference in 1955 to the decision to join the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961. Here is where we, probably, find a weak spot in his policies, a recurring feature in many intelligent people. Makarios was very confident in his mental faculties and therefore believed he could pursue a flexible policy, darting between the great powers – a perilous balancing act. As it turned out, his genius, as capable as it was, could not counteract the huge risks facing a small country in the most volatile region on the planet. Especially when his genius could not be perceived by the stupidity of Ioannidis.

This characteristic explains the greatest mistake Makarios made during his long tenure: inducting Cyprus into the Non-Aligned Movement. The Karamanlis government had enthusiastically encouraged Cyprus’ induction into the West, into NATO, and if that was too difficult a task, the growing European Economic Community. Makarios did not heed this advice, believing that by joining the Non-Aligned Movement he strengthened his hand when dealing with the great powers. However, Cyprus could not ensure its security by joining the institutional framework of the Third World: A Turkish invasion of a Western member-state was inconceivable; however, an invasion of a non-aligned country was not.

In any case, he was the most internationally known leader of Hellenism of the modern era. No one, from Ioannis Kapodistrias and Eleftherios Venizelos to Karamanlis, enjoyed Makarios’ fame, his constant presence in academic debates and on newspaper front pages, or even in the memory of the everyman. Makarios was immortalized in the wax sculpture collection of Madame Tussauds, precisely because he had a certain level of fame with the average European or American that no other Greek politician had. Another example is a reference to Makarios along with other decolonization leaders in the BBC’s satirical comedy “Yes, Minister” in 1981, four years after his death and 25 years after he was deported by the British colonial authorities. “The letters ‘JB’ are the most outstanding honor in the Commonwealth. They stand for Jailed by the British. Gandhi, Nkrumah, Makarios, Ben Gurion, Kenyatta, Nehru, Mugabe. The list of world leaders is endless.” They were all, of course, leaders of Third World countries…

Historical impact

Makarios is no longer the type of leader needed for Hellenism in the 21st century, whether Greek or Cypriot. Ethnarchs were leaders of an unorganized nation – of a people on the cusp of change – while Hellenism today is part of the Western world and is institutionally organized. Nevertheless, Makarios’ historical impact remains unprecedented. The aura he exuded exceeded the sum of his decisions and is a product of various situations. Firstly, he was a manifestation of a tradition going back centuries, a tradition both spiritual and political, much older than the stately traditions of his international peers. Especially at the time, when European and Western elites were still heavily classically educated, it was inconceivable to show arrogance to the cinnabar signature granted to the archbishop of Cyprus in the late 5th century AD. Secondly, it was important that, despite being a man of the cloth and known to espouse conservative political views (his pro-monarchy stance was well-known), internationally he represented a revolution (1955-59) and later the Non-Aligned Movement, that is an endeavor by the poorer nations on the planet seeking to redistribute its wealth. Finally, his personality and personal skills were very impressive, anchored in the knowledge of the long historical tradition his position represented. These made him a captivating public figure, an unprecedented phenomenon on the international scene.

Professor Evanthis Hatzivassiliou teaches contemporary history at the University of Athens and is general secretary of the Hellenic Parliament Foundation for Parliamentarism and Democracy.