Newsroom

Sirens pierced the morning calm across Cyprus at exactly 8:20 a.m. on Monday, marking 51 years since the July 15, 1974 coup that would change the island forever.

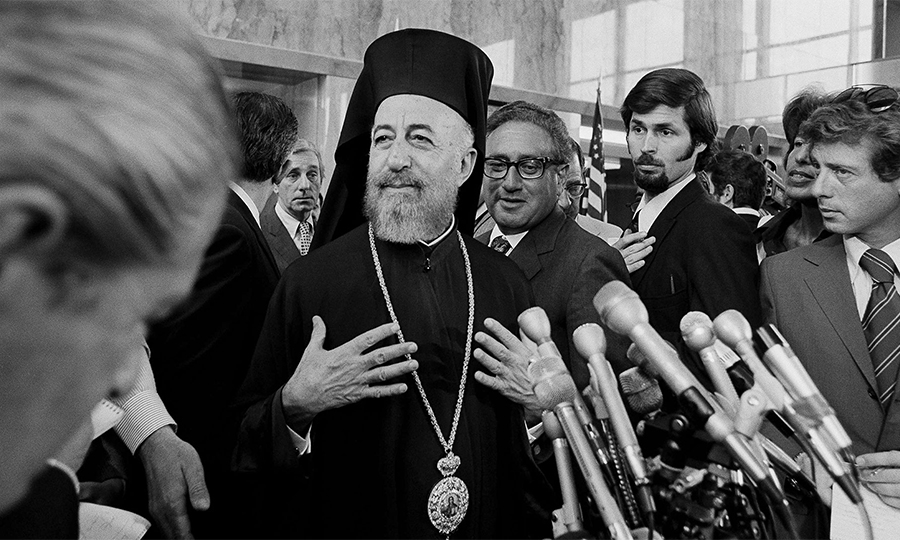

The eerie wail of the sirens, which sounds annually at the exact hour the Presidential Palace came under fire, is more than just a ritual. It is a stark reminder of the day the elected president, Archbishop Makarios III, was violently overthrown in a military coup engineered by the Greek junta, an event that paved the way for Turkey’s invasion and the enduring division of Cyprus.

A coup in broad daylight

According to declassified documents from Greece’s Central Intelligence Service (KYP), made public for the first time by Greece’s National Intelligence Service (EYP), there was little warning of the chaos that would erupt that Monday morning in 1974.

Just two days before the coup, on July 13, Archbishop Makarios gave an interview to Britain’s ITN network, calmly downplaying any suggestion of danger. “The situation in Cyprus is not critical unless the Greek government is determined to create conditions for civil war,” he told journalist Michael Nicholson. When Nicholson asked if he should stay on the island over the weekend “in case something happened,” Makarios brushed it off. “Nothing will happen. I am perfectly safe.”

But at 8:30 a.m. on July 15, all illusions of calm were shattered.

Armored units of the National Guard stormed the Presidential Palace in Nicosia. The Presidential Guard and police forces mounted resistance, but by mid-morning, the state broadcaster, CyBC, had been taken over. A chilling message aired across the country: Makarios was dead, and a new “National Salvation Government” under Nikos Sampson had been installed.

Makarios, however, was very much alive.

He had fled through the mountains, briefly taking refuge in Paphos before being airlifted to safety by the British. By July 19, he stood before the United Nations Security Council in New York, denouncing the coup and warning the international community of what would come next.

“It was my mistake to trust them.”

In his speech at the UN, Makarios pulled no punches. “It was the Cypriot government that invited Greek officers to man the National Guard. I regret to say that it was my mistake to place so much trust in them. They abused that trust and instead of helping to protect independence, they undermined it.”

The declassified bulletins from KYP reveal that even Greece’s own intelligence apparatus had not anticipated the scope of the operation or its consequences. The same day of the coup, they reported that “the situation in Cyprus is fully under control,” and that resistance was minimal.

But as history would prove, that “control” was short-lived.

Just five days later, Turkey launched a military invasion, citing its right as a guarantor power to protect Turkish Cypriots. The invasion resulted in the occupation of the northern third of the island, a division that remains to this day, with Turkish Cypriots controlling the north and the internationally recognized Republic of Cyprus governing the south.

Echoes still heard today

Each year, the July 15 sirens echo through cities and villages across the island. For many Cypriots, Greek and Turkish alike, they are not only a tribute to memory but also a call for reflection on what was lost and what remains unresolved.

For expats and younger generations who didn’t live through it, today serves as a somber history lesson: that peace and democracy can be fragile, and that trust, once broken, can alter the course of nations.